First and foremost, any digital history project requires data in a machine readable format. How to find enough digitized data has been a big struggle for digital history. Some historians use large government datasets, but these rarely go back more than a few decades. Others use already digitized corpuses, like newspapers from the 19th century, or born-digital materials, such as tweets or digitized journal articles. However, for historians of the mid-20th century like myself, there is generally an absence of publicly available corpuses of digitized data because of copyright restrictions.

In my opinion, one of the most exciting aspects of this project is the prospect of using archival sources that are not under copyright. However, even with the prospect of sharing declassified government documents, there still remains the challenge of digitizing these materials.

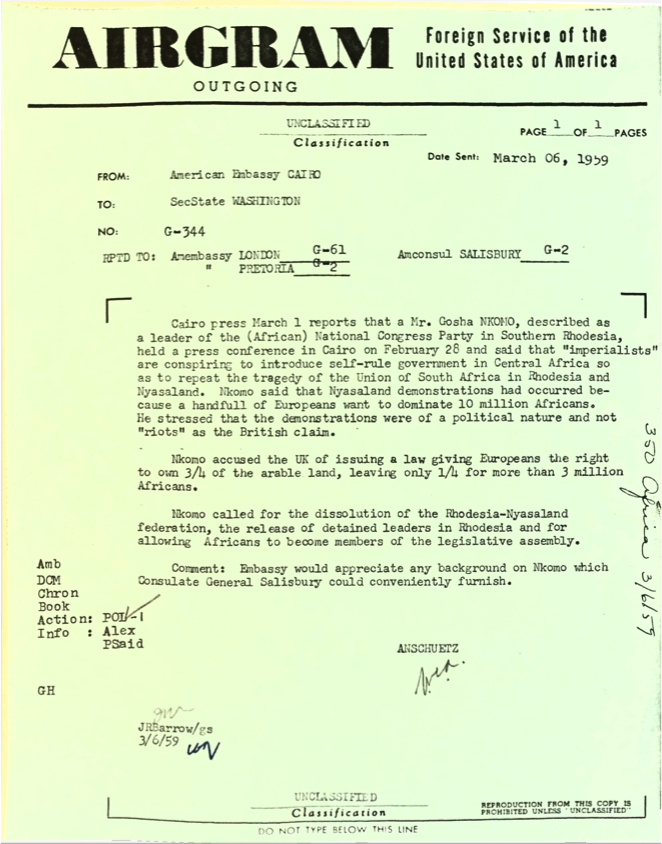

Making an image into a machine readable document requires using a program to run optical character recognition on the image, which essentially extracts the text from the image. In the last few years, OCR has made huge strides. However, many of these programs still focus solely on text, which means any images in a document usually gets discarded. For diplomatic cables, there aren’t many images, but for other sources this absence can be a drawback.

Some of the free OCR options include Google’s Tesseract and Overview Docs. However, after being referred by Micki Kaufman and trying it out myself, I highly reccomend Abbyy FineReader Pro for Windows. I’ve tried the program on Mac and the results are less impressive. Whereas, the Windows version is extremely accurate for clear text in Romantic languages, and even works on my Arabic sources depending on the font. At the moment, the majority of relatively clear text produces close to 95% accuracy in the OCR process. One of the struggles in undertaking this project was that sometimes the photocopies of the diplomatic cables were fuzzy, which lessened the ability for Abbyy FineReader to pick up the text. My current solution is to initially process the text, and then hopefully go back later to make corrections manually. The process is a tedious, but each correction helps improve the overall analysis.

Cleaning your data is one of the most time consuming aspects of any digital history project, and is why increasingly historians are turning towards sharing data. One of my final arguments in my SHAFR 2016 presentation is that diplomatic historians should start considering sharing their images and scans of diplomatic cables.

After spending a few months at NARA last spring, I couldn’t help but look around the reading room and seeing the majority of patrons using some type of digital collection device, wonder why we don’t share these materials. I realize there are a number of reasons, not the least that after spending a few months at College Park, you don’t want to give away all your hardwork for free. However, for mid-twentieth century historians there seems to be an opportunity to exchange materials since no one person can ever photograph all the sources contained at NARA.

I think one way we could share is through Overview Docs, which lets your share datasets. However, I’m not sure Overview Docs let’s you share images and having the original unprocessed image might also be useful. Another alternative is academictorrents, which lets you share large datasets of any filetype.

Ultimately, the technical challenge of sharing materials is minor compared to changing our culture of conflating archival sources with our interpretaions. If historians, and especially diplomatic historians, are ever going to share materials, I think we’ll have to craft a system that benefits everyone through enabling attribution for datasets and exchange of materials between historians. These thoughts are just some earlier ruminations, but I hope others are interested in this issue. If you want to talk more, please feel free to reach out to me on the About page.